Summary

In recent years, California policymakers have made a number of cuts to major safety net programs to help balance the state budget-even as hard economic times have meant that increasing numbers of Californians are relying on government assistance. The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids program (CalWORKs) has been one of the most affected.1 Since 2009, CalWORKs has seen a number of cuts, some intended to be short-lived, and others that, arguably, are reshaping the program piece by piece. In his January 2012 budget proposal, Governor Brown advocated significant additional cuts. These recent and proposed changes raise questions about the program’s goals going forward.

What Is CalWORKS?

CalWORKs is both a child well-being and a welfare-to-work program. It has two central goals. The first is to buffer children against extreme poverty by supplementing family income.2 Low-income families who apply and are determined to be eligible receive a monthly cash grant pegged to income level and family size. Every three months they must file paperwork demonstrating their continued eligibility.3 In September 2011, just after the most recent round of budget cuts took effect, the average monthly grant was $458.4

In September 2011, just after the most recent round of budget cuts took effect, the average monthly grant was $458.

CalWORKs’ second goal is to increase parents’ earning power and thus help them gain independence from welfare. (Childless adults are not eligible.) To that end, many parents who receive assistance must either work or engage in a specified set of activities intended to lead to employment. These parents receive “welfare-to-work” services to help them find and keep jobs. Work services can include job search assistance, job training, and vouchers for transportation and child care.

Parents can be excused from work requirements-if, for example, they have a young child or primary care of a disabled family member. These exempted parents are eligible for a monthly grant but they do not typically receive work services.

Parents can become temporarily or permanently ineligible for cash grants. When they are ineligible for a grant, they usually do not receive work services. They become ineligible if they do not comply with work requirements and lack a proper exemption, or when they have received 48 months of assistance as adults. Unauthorized immigrant parents of citizen children and those who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) assistance are never eligible for CalWORKs.

In keeping with CalWORKs’ goal of safeguarding children’s well-being, children do not lose eligibility if their parents are, or become, ineligible.5 Many children receive CalWORKs grants while their parents do not.

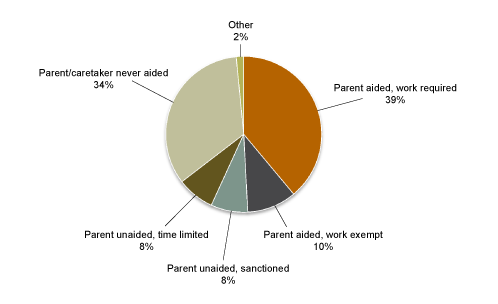

In 2009, an average of 39 percent of families receiving a CalWORKs cash grant included parents who were required to work and entitled to work services (Figure 1).6 Of the rest, approximately equal shares of parents received aid but were exempted from working, were temporarily ineligible for aid, or were permanently ineligible because they had reached their time limit. Thirty-four percent of CalWORKs families included parents (or other caregivers) who had never been eligible for assistance.

FIGURE 1. In 2009, about half of CalWORKS parents were ineligible for grants and work services

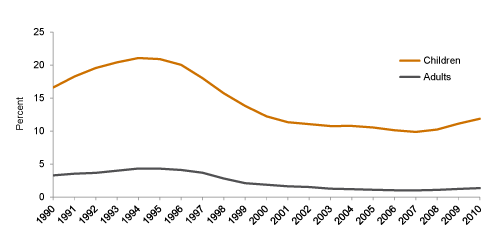

Currently, CalWORKs provides cash assistance to approximately one in eight California children and a much smaller share of parents. The share of children receiving aid is higher than it has been in a decade, which reflects persistently high unemployment rates in most parts of the state, but remains far below the 1990s caseload peak (Figure 2).7 Also, in inflation-adjusted terms, the maximum amount of monthly cash assistance has been cut roughly in half since 1990.8

FIGURE 2. The percent of parents and children aided by CalWORKS grew during and after the Great Recession

The Origins of CalWORKS

The 1990s saw a major restructuring of states’ cash assistance programs. States increasingly obtained permission to alter federal rules and pursue their own program goals.9 California used this largely as an opportunity to further emphasize-and reward-work.

Taking state experimentation a step further, in 1996 the federal government created a welfare program called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).10 The catchphrase was that it would “end welfare as we know it”

Officially rolled out in 1998, California’s CalWORKs program continued the state’s work-first approach; it also gave counties additional authority to design their welfare-to-work services.11 Today, the federal government provides more than half of the CalWORKs budget but the program’s scope and purpose are substantially under state and county control. As long as state policymakers treat similar families equally, they can set the level of cash grants. They also have leeway to determine the level of work services, along with other program policies, such as the number of months a parent can receive assistance.

Notably, federal law allows the state to redirect CalWORKs funds from cash grants and work services to related, but non-CalWORKs, programs.12 This means that funds for CalWORKs grants and services are vulnerable in tough budgetary times.

CalWORKS in Transition

The first decade of California’s CalWORKs program saw decreases in grant amounts (after adjusting for inflation) but no reduction in work services. Beginning in 2009, yearly budget cuts further reduced monthly grants and began to reduce work services. Together, these cuts have constrained the program’s original aims.

Beginning in 2009, yearly budget cuts further reduced monthly grants and began to reduce work services.

Cuts to grants took three forms. First, starting in July 2011, the state shortened the time limit from 60 to 48 months, reducing the number of parents eligible for CalWORKs. Second, the state made across-the-board reductions in grant payments. Third, working parents on CalWORKs began to see smaller grant amounts, lessening their incentive to work.

The state also changed its policy so that fewer parents were required to work and cut county funding for work services. Specifically, parents with one child under age two or two children under six have been temporarily exempted from the work requirement. Previously, children had to be much younger for parents to qualify for an exemption. The upshot of this policy change? Counties save money on work services.

Governor Brown’s 2012 Proposal

The governor’s January budget proposal includes further reductions for CalWORKs. Once again it proposes cutting both grant amounts and work services-but this time there are several major twists.13 The governor proposes to concentrate resources on families that have been receiving assistance for a relatively short period and families with parents who are working.

The budget proposal divides CalWORKs recipients into three groups. In the first group, called CalWORKs Basic, are families with eligible parents in their first 24 months of CalWORKs assistance (over their adult lifetimes). The second group, CalWORKs Plus, includes families with eligible parents who are working a substantial number of hours in private employment before they reach their 48-month time limit.14 Most work services would be reserved for CalWORKs Basic and CalWORKs Plus families. In addition, changes in the grant formula would modestly increase the amount of cash assistance retained by families in CalWORKs Plus.15

All other families would be placed in a new Child Maintenance program. All parents in this program would be ineligible for cash assistance. In addition, grants to children in these families would be sharply curtailed (by an average of 27%). Finally, work services for this group would shrink drastically. For example, parents eligible to move to CalWORKs Plus could receive only one month of child care every six months to help them search for a job.16 Parents with more than 48 months of assistance could receive work services (but not cash assistance) only when they met a minimum required number of hours in private employment. These changes would further reduce the share of parents receiving CalWORKs cash assistance and work services.

The Path Ahead

Recent cuts to CalWORKs-to grant levels, to the availability of work services, to time allowed on the program-could be rolled back, but this would require additional state funds. The governor has proposed instead to continue on a reduced path, focusing services on relatively work-ready families and decreasing resources to children whose parents are ineligible or become ineligible.

What would CalWORKs be like if the governor’s proposal were to become law? For those who make relatively brief use of CalWORKs-the majority of those who rely on welfare over the course of their lives, but the minority of the caseload at any one point in time-the program might not appear to change much. For those who work substantial numbers of hours for private employers and do not exceed 48 months of assistance, the generosity of the program would actually increase. But the rest would experience a sharp curtailment.17

What would CalWORKs be like if the governor’s proposal were to become law?

The governor’s proposed changes are substantial. In effect, they reopen a discussion about the main purposes of this program that was last held when CalWORKs first began.

Two key issues are in play. First, who should have access to CalWORKs work services? Those who are more likely to find and keep a job, or those who need intensive support to have much, if any, hope of becoming stably employed? Or both? Second, how much of a safety net should CalWORKs provide for children whose parents cannot or do not work?

Trade-offs between CalWORKs’ goals of immediate income support and longer-term self-sufficiency are embedded in the program as it currently exists. Policymakers need to consider these trade-offs carefully. With enormous potential changes on the horizon, it is perhaps time to take stock-to revisit CalWORKs’ overall goals and to address fundamental questions about the kind of program California wants to provide to families in need.

Related Resources

Hamilton, Gayle. 2002. Moving People from Welfare to Work: Lessons from the National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/newws/synthesis02/.

Holzer, Harry, and Karin Martinson. 2008. Helping Poor Working Parents Get Ahead: Federal Funds for New State Strategies and Systems. Washington DC: Urban Institute. Available at www.urban.org/publications/411722.html.

Loprest, Pamela, and Austin Nichols. 2011. Dynamics of Being Disconnected from Work and TANF. Washington DC: Urban Institute. Available at www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412393-Dynamics-of-Being-Disconnected-from-Work-and-TANF.pdf.

Morris, Pamela, Virginia Knox, and Lisa A. Gennetian. 2002. Welfare Policies Matter for Children and Youth: Lessons for TANF Reauthorization. New York: NY: MDRC. Available at www.mdrc.org/publications/183/policybrief.html.

Reed, Diane F., and Kate Karpilow. 2010. Understanding CalWORKs: A Primer for Service Providers and Policymakers. Sacramento: California Center for Research on Women and Families. Available at www.ccrwf.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/ccrwf-calworks-primer-2nd-edition.pdf.

Zedlewski, Sheila, Ajay Chaudry, and Margaret Simms. 2008. A New Safety Net for Low-Income Families. Washington DC: Urban Institute. Available at www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411738_new_safety_net.pdf.

Zellman, Gail L., Jacob Alex Klerman, Elaine Reardon, Donna O. Farley, Nicole Humphrey, Tammi Chun, and Paul Steinberg. 1999. Welfare Reform in California: State and County Implementation of CalWORKs in the First Year. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. Available at www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1051.html.

Topics

Health & Safety Net